Table of Contents

The Vagus Nerve: A New Frontier of Brain-Body Medicine

Research into the vagus nerve is revealing why traditional approaches to well-being were so effective.

BY AMY DENNEY TIME JUNE 9, 2022

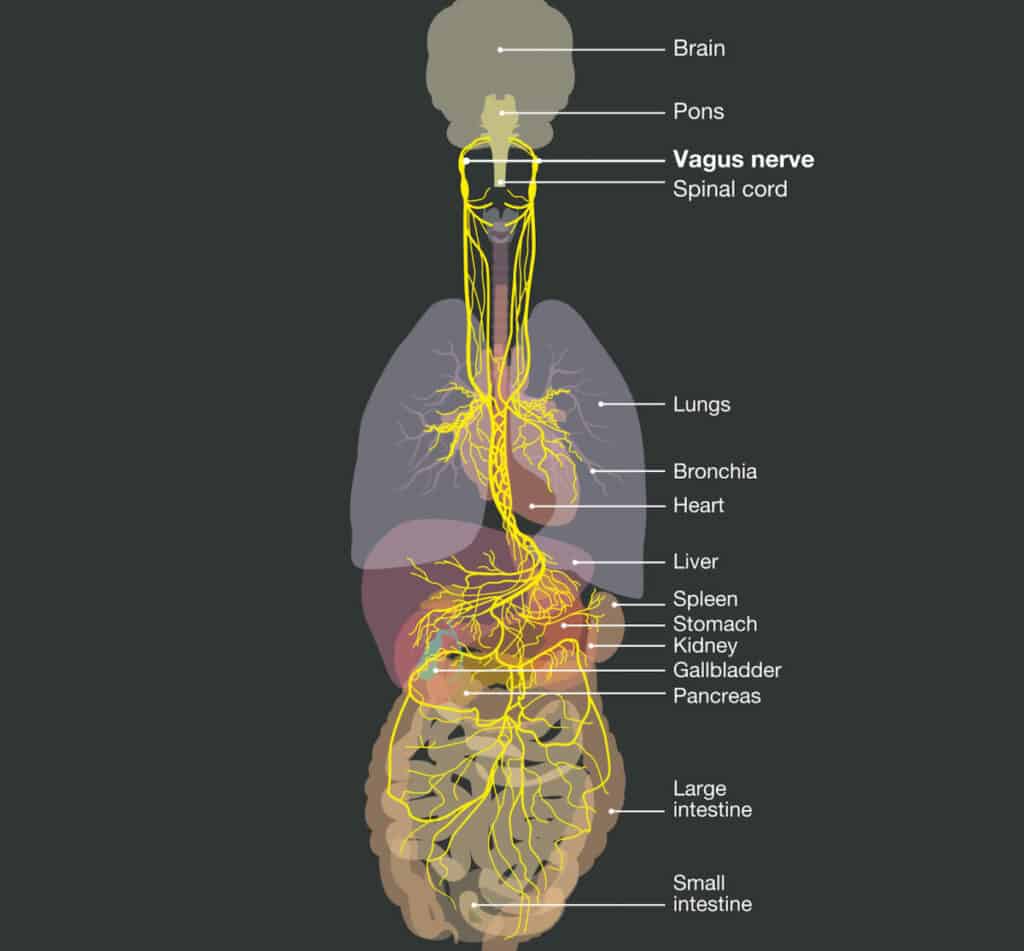

To access the benefits of body-brain medicine, you may want to familiarize yourself with the vagus nerve, which is a two-way communication system between the brain and your organs.

The 10th of the 12 cranial nerves, the vagus nerve is responsible for regulating emotional and physiological well-being.

It’s the longest nerve in the autonomic nervous system—actually, we have two, one on each side of the body that weaves through the torso and neck. Vagus is Latin for “wandering,” aptly named, as this nerve communicates both sensory and motor information from several systems and many organs.

Because it’s associated with blood vessels, the lungs, the heart, the stomach, the esophagus, and the intestines, the vagus nerve regulates circulation, breathing, heart rate, digestion, and other areas of our physical health.

Anti-inflammatory

The vagus nerve is considered by many researchers to be “anti-inflammatory,” because it can regulate inflammatory responses when it’s working optimally.

When it comes to digestion, the vagus nerve controls many aspects of the process, including assisting the pancreas in releasing digestive enzymes, helping the gallbladder nudge out the correct amount of bile, and controlling the valve at the base of the stomach, as well as the one in between the small and large intestines.

About 80 percent of the fibers of the vagus nerve run from the body to the brain. This fascinating fact is what leads to “bottom-up” approaches in cognitive-behavioral research and practice. While it may be impossible to talk the brain out of a behavior (top-down therapy), practices that involve the body and tapping into the vagus nerve can send messages of safety, tolerance, and confidence to the brain. This bottom-up approach has been found to be particularly helpful for triggers and even for managing physical symptoms of disease and illness.

Polyvagal Theory

Polyvagal theory, or how the many (poly) branches of the vagal nerve connect to numerous organs, was first presented by Stephan Porges in 1994. Over the next decade, it started gaining acceptance in trauma therapy by pioneers who recognized the effectiveness of body-based approaches in the treatment of trauma.

In a normally regulated person, the body’s autonomic nervous system easily moves between the sympathetic—the “gas pedal” of arousal that can assist us in fighting or fleeing—and the parasympathetic—the “brake” that gives our systems the chance to slow down for resting and digesting our food.

Someone who has a dysregulated nervous system often feels victimized by the overly exaggerated states that either put them in perpetual hyperarousal or leave them completely numb—or stuck on a pendulum, swinging between the two. Not only can this undermine relationships, but it can also wreak havoc on the immune system and contribute to developing diabetes, heart disease, gut issues, and more.

Functional doctors often describe this in terms of vagal tone—how well your body self-regulates. Higher heart rate variability means you can regulate the beats of your heart, even when you’re facing stress, and your body and emotions can respond in a calm way. Low vagal tone indicates prolonged stress, anxiety, depression, and emotional dysregulation not only during stress, but also when the trigger is no longer present.

Polyvagal theory continues to change the landscape of psychology and is making its way into biology.

As Bessel van der Kolk wrote in his bestselling book, “The Body Keeps the Score,” polyvagal theory “made us look beyond the effects of fight or flight and put social relationships front and center in our understanding of trauma. It also suggested new approaches to healing that focus on strengthening the body’s system for regulating arousal.”

This deeper understanding of the nervous system is spurring a growing field of research. With that has come a renewed comprehension of the connectedness of body and brain and how this connection affects healing. While many traditions and philosophies from humanity’s past held this connection as a medical fact, it was widely forgotten in the modern era. Now that researchers have gained a physiological explanation and quantifiable data around the mind-body connection, it’s again being applied in broader physical health care disciplines and communities. It underscores the need for a more holistic approach to healing.

That’s what got the attention of Terry Powley, a Purdue psychological sciences professor, who has studied the vagus nerve for decades, shifting his attention from the brain to the gut.

Gut Health

His goal is to expand therapeutic applications of vagus nerve stimulations specifically to improve gastroparesis, a condition that affects the muscles of the stomach, preventing proper emptying and resulting in painful symptoms for patients. The vagus nerve is responsible for stimulating the muscles of the digestive tract. But because this nerve is involved in so many bodily functions, it can be hard to untangle different aspects. Figuring out exactly how to isolate the stomach from the heart is a critical area of research that can lead to better treatments for patients.

Powley is part of an international team involved in a six-year, $13.5 million study of the vagus nerve’s connection to the stomach. Purdue’s project to map the stomach nerves’ circuitry and function is contributing to the National Institutes of Health’s SPARC (Stimulating Peripheral Activity to Relieve Conditions) initiative.

Launched in 2016, the SPARC grant has allowed scientists to get more specific information about the vagus nerve using an electron microscope. This tool allows researchers to more accurately determine the body’s bioelectric methods of stimulating the stomach, insight that can assist in future treatments. The grant expires this summer, but it has launched a $9.8 million prize competition for concepts and plans to develop clinical solutions for targeting select nerves without unintended effects on surrounding organs.

Among the tools and technology highlighted by SPARC is infrared light therapy, which uses specific frequencies of invisible light to direct heat and energy to spots inside the body.

I had never heard of infrared light therapy personally until several years ago, when my husband experienced severe gastrointestinal pain. He saw several specialists over the course of a few weeks, and while a CT scan indicated a potential mass in his intestine, two scopes determined there was nothing there.

Of course, he didn’t feel like there was nothing wrong, but he was dismissed for lack of additional treatment. At that point, he had already lost 40 pounds because eating and drinking had become increasingly painful. He was hardly sleeping, and he was unable to work at all.

A physician and friend of mine who had recently experienced gastroparesis as a side effect of cancer treatment recommended low-level light therapy for my husband. After three sessions using LED light pads on his gut, motility was restored, and eventually, normal function returned.

Near-infrared light dilates blood vessels by increasing nitric oxide at the cellular level. Circulation improves and sensation returns as tissue is regenerated. Researchers typically describe this treatment as “photobiomodulation” or “infrared light therapy,” and there are thousands of studies and papers looking at its efficacy in the National Institutes of Health’s PubMed.gov database.

One of the many functions of nitric oxide is to release acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that plays a role in the autonomic nervous system, especially important in bringing the body into a parasympathetic state. Separate from the vagus nerve, but equally important for the health of the brain and gut, acetylcholine production begins to decline with age.

The roles that the vagus nerve plays in physical healing may not ever be completely understood, but researchers are trying to develop technologies that will let them create effective treatments. SPARC researchers are accelerating the development of tools and technology that modulate activity in the nervous system and improve organ function. Besides light waves, some of those are electrodes, ultrasound, biosensors, and electrical currents.

There are plenty of low-tech tools that are also getting attention in research and in practice. They include nutrition, somatic practices, supplements, and breathing practices.

One study of irritable bowel syndrome patients found that those given relaxation therapy experienced a significant decrease in pain, as well as lowered stress levels and improved quality of life.

Other approaches that have shown clinical improvement with stomach issues include mindfulness-based programs, yoga, hypnotherapy, and mind-body interventions.

The vagus nerve is simply one component of a complicated gut-brain interaction that also involves the endocrine, immune, and humoral systems. However, studies show an influential connection between vagal tone and food intake, weight gain, inflammation, and homeostasis. It can even help with the regulation of satiety and energy.

“Vagus nerve stimulation and several meditation techniques demonstrate that modulating the vagus nerve has a therapeutic effect, mainly due to its relaxing and anti-inflammatory properties,” according to a research review article published in Frontiers in Psychiatry in 2018.

While urban lifestyles are contributing to a rise in environmental stressors and toxins that disturb the mind-body balance, we have many tools at our disposal to retune ourselves. While technology may soon offer new therapies, we can also tap into intuitive ancient practices that can undo the damage and prevent further inflammatory assault.